Haskell-based Development Environment

In a previous post I described the overall design and architecture of Capital Match’s core system. I now turn to providing more details on our development and operations environment which uses mostly Haskell tools and code. As there are quite a lot of moving parts, this large topic will be covered in two posts: The present one will focus on basic principles, build tools and development environment ; it shall be followed by another post on configuration management, deployment and monitoring. I consider both development and production environments as a single integrated system as, obviously, there is a porous membrane between the two especially in a small company with 4 developers. Although I have been interested in that topic since my first systems programming course in university, some 18 years ago, I do not consider myself a genuine systems administrator and I made a lot of mistakes while building Capital Match platform. But I do believe in the “you build it, you run it” motto and this is all the more true for a small startup team. Hence I have tried to pay attention to building a flexible yet robust system.

Principles

When we started to setup this environment, we were guided by a few principles:

- Automate, automate, automate: As much setup as possible should be automated,

- Every system-level part should be containerized,

- There should be a single versioned source of authority for configuration,

- Use as much Haskell as possible.

Automate

Automate all the things!

Deployment to production should be as much automated as possible, involving as few manual steps as possible. The end goal is to reach a state of continuous deployment where pushed changes are built, verified and deployed continuously over the day. This implies all the steps involved in getting some feature delivered to end-users should be identified and linked into a coherent process that is implemented in code, apart from the actual coding of the feature itself. There should be no fiddling with SSHing on production machine to fix some configuration script, no manual migration process when upgrading data schema, no copying of binaries from development environment to production…

Everything Docker

Containerize all the things!

docker is still a controversial technology, esp. among system and cloud specialists, and the topic of hot debates which is a sure sign it is a game changer. And back in 2014 when we started developing Capital Match’s platform, docker was in its infancy. I have had some experience in the past working with VServer and LXC and containers are definitely great as a way to package (parts of) a system. Using docker allows us to:

- Provide seamless integration of development and production environments: The exact same software can be produced anywhere and used anywhere, whatever OS or configuration the actual developer is using, and the production configuration can be reproduced easily for testing or staging purposes,

- Encapsulate components in immutable “packages” that require minimal system-level configuration, e.g. no more fiddling with ports, machine names, environment variables… docker-compose takes care of running everything, and we can make services dependent to stable names,

- Simplify “hardware” configuration: All we need is something that is running docker (and a compatible kernel of course…) which means machines provisioning becomes a no-brainer,

- Isolate build and run components from system-level dependencies conflicts,

- Provide some level of reuse across containers and components thanks to layered FS.

Note that we stuck to the initial docker “philosophy” of one process per container, except for some very specific needs (e.g. Selenium testing): It is not possible to ssh into our applicative containers.

Single Source of Authority

Version all the things!

This means we should of course version our application’s code, but also the system’s configuration and as much dependencies as possible. Ideally, we should be able to reconstruct the whole system from a handful commands:

git clone <the repo> cmcd cm; ./build ; ./deploy

In practice this is quite a bit more complicated as there are some glue parts missing to ensure the whole system can be rebuilt from scratch, but still we came quite close to that ideal. We are using 2 different repositories, one for the application code and one for the environment, mostly for technical reasons related to how our configuration management software works. The only unversioned part is the description of the “hardware” and the provisioning part which is still done “manually”.

Everything Haskell

Typecheck all the things!

There is not a dearth of tools when it comes to configuration management, systems provisioning and deployment, build tools… When starting small you usually don’t want to invest a lot of time in learning new tools hence a common choice is simply to start small with shell scripts. But tools usually exist for a reason: Scripts quickly become a tangled maze of scattered knowledge. Yet we have at our disposal a powerful tool: Haskell itself, the language and its ecosystem, hence we decided to try as much as possible to stick to using Haskell-based tools. Beside the obvious simplification this brings us (one compiler, one toolchain, one language…), the advantages Haskell provides over other languages (type safety, lazy evaluation, immutable data structures) seemed to be equally valuable at the applicative level than at the system level.

Overview

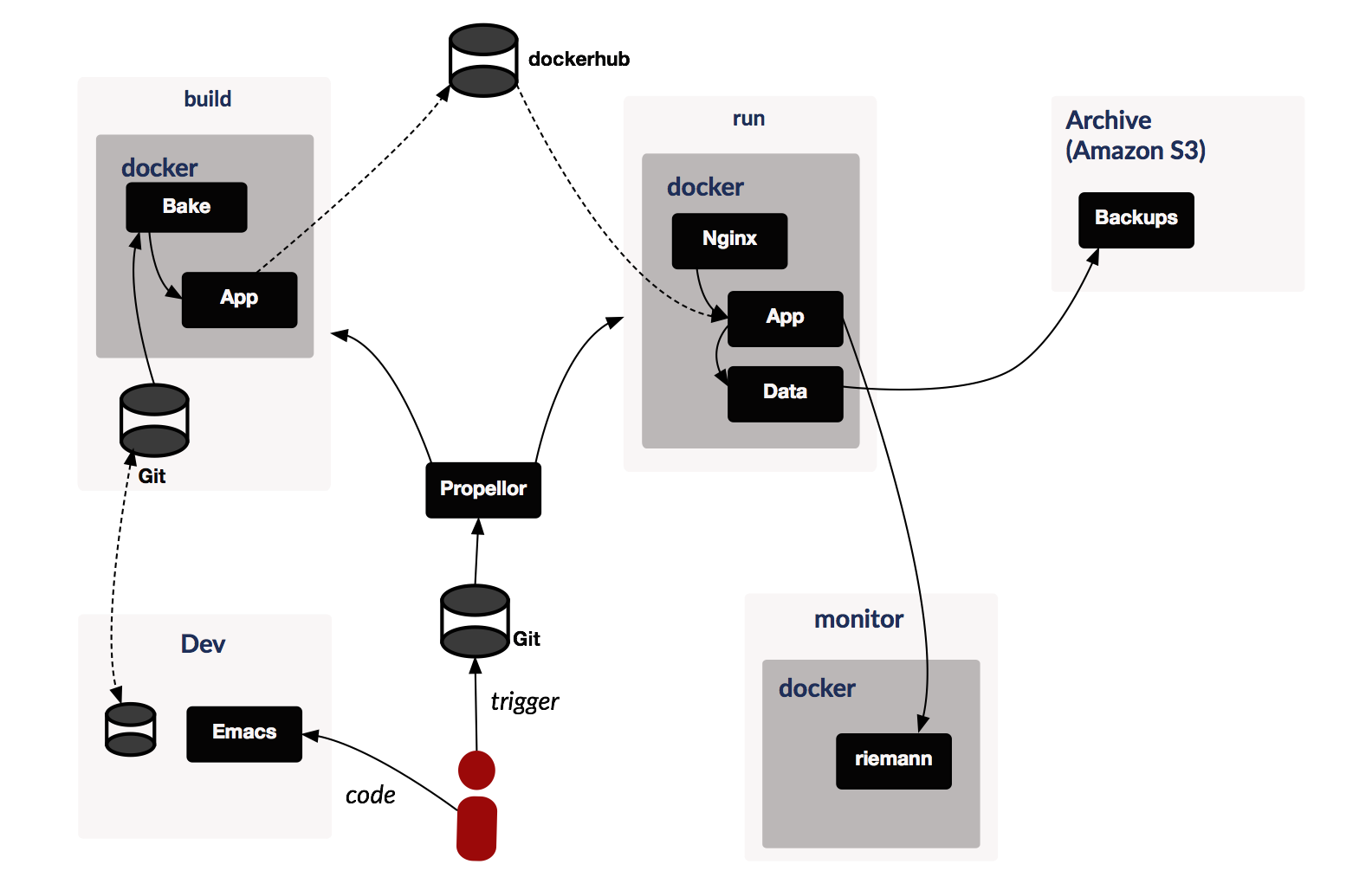

The above figure gives a high-level overview of the system:

- Developers work on local machines (or dev boxes, see below), pushing changes to git,

- Pushing to remote repository triggers build on continuous integration server bake,

- The final output of CI is a bunch of containers which are deployed to a private repositories on docker hub,

- When we are ready to deploy, we update the system configuration in another git repository then run propellor,

- This triggers configuration of run system which usually entails downloading correct container from repository and running it,

- Data (also stored in a container) is regularly backed-up on S3,

- Various components of the system feed events to riemann monitoring system.

Build & Toolchain

Build

Cabal

For building the Haskell part, we started obviously with Cabal which is the defacto build system/package manager in Haskell. The structure of GHC+Cabal packages system makes it quite hard to create insulated and reproducible build environments as there are various interactions between what’s installed globally (with GHC) and what’s installed per user and per project. There was no stack two years ago so we had to roll our own. Here are some key features of our cabal-based build:

- We used cabal snapshots with pinned down versions of all dependencies through

cabal freeze - Build became more complex when we started to add subpackages and sharing dependencies (>100) seemed like a good idea. We shared a single sandbox by setting

CABAL_SANDBOX_CONFIGto point to toplevel directory sandbox configuration file for all packages, thenadd-sourcesub-packages. This make it easier to simultaneously:- Build everything in one go,

- Work in a sub-package,

- Work in main (top-level) package,

- This does not prevent rebuilds when moving across packages as the build directory used by cabal is still located within each package,

- We are still dependent on a globally available GHC. When upgrading GHC versions, you need to change globally installed GHC before rebuilding,

- Several concurrent versions can coexist and be used in the same directory as GHC maintains version/OS dependent packages database, but care need to be taken with

PATHs as the cabal version is likely different too…

Stack

stack represented a huge improvement for managing our build but it took us a few months to ensure it built consistently.

- Stack provides truly repeatable builds and segregate build environments tightly, including the tooling (compiler, lexer, parser…), managing downloads, setting package databases paths…

- There is a single executable to install which makes creating build containers much easier: install stack, run setup and you have a fully configured container at required version. It is also very easy to upgrade,

- Stack manages dependencies through stackage meaning you only have to provide a single version number and you are guaranteed to have compatible versions of libraries. This might be sometimes problematic if you require some specific version of a library that is not part of the dependency package, but it is still possible to provide custom versions,

- I was sometimes surprised by stack not reusing some previous build result, although I could make it work manually,

- The biggest hurdle we had to overcome to make stack work for us were the tests. Some tests relied on specific files to be present which means we had to manage relative paths: depending on whether or not tests are run from toplevel (which is the case in CI for example) or from local package directory (which is the case when using stack to build a tree of packages), relative directory may not be correctly set. Moreover stack runs tests in parallel, which is a good thing to force you to implement parallelizable tests but failed for us as we relied on starting server on some port for integration tests. We should get rid of hardwired port and allow the server to use some randomly allocated one but we chosed the simplest path and configured stack to run tests sequentially.

- A minor annoyance is (was?) that stack maintains a build directory in each sub package, even when run from the toplevel, which is not the case when using cabal sandbox. This implies that reusing previous builds is a bit more cumbersome as one needs to save each

.stack-workdirectory.

Leiningen

leiningen is (was?) the prominent build tool for clojure and clojurescript. We chose Clojurescript for the UI mostly because this allowed us to develop it using the excellent Om wrapper over React. It took us quite a lot of time to get our project build comfortable and it did not evolve as quickly as the Haskell one.

- When to distinguish various build targets: Development mode where we want some interactive reload within the browser, test mode to run unit tests (automatically or in batch) and production mode which needs to be optimiszed,

- Getting the tests to run correctly proved difficult and is still dependent on some manual configuration: To run clojurescript tests, we need to install phantomjs and configure correctly externs for the few javascript libraries we use and compile both code and tess with only whitespace optimizations (tests don’t run in fully optimized mode),

- This actually means code is compiled as much as 3 times, which takes some time…

- The CSS part of the UI is written using garden, which means we have to compile it to proper CSS then pack and compress all CSS files together to improve load time. In retrospect, this was probably a mistake: We don’t use clojure’s power to write our CSS and it is still a mess, so we would have been better off using some standard CSS language like Less or Sass (although this adds the burden of running some thirdparty tool as part of the build…).

Javascript

When we introduced the mobile UI for Capital Match, we had to integrate its build inside our process. This caused some headache as this part of the system is developed in pure Javascript using Emberjs and relies on various tools in the JS ecosystem I was not familiar with. It also used sass to write CSS which means we needed ruby to run the compiler.

- We packaged all system-level dependencies into a single docker container. Note that official distribution’s package for node and npm were outdated hence we had to install them “by hand” in the container which is apparently the right way anyway,

- There is a single top-level script which builds everything and is ran from the container.

Shake

Given the diversity of tools and components we are building, we needed a way to orchestrate build of the full solution which could be easily run as part of Continuous integration. We settled on shake which is a Haskell-based tool similar to make.

- Rules are written in Haskell and shake provides support for all system-level tasks one would need to do in a build, including running arbitrary processes, manipulating their output, manipulating files… Using this embedded DSL makes it possible to track dependencies more easily. Shake maintains a database of dependencies that can be populated with arbitrary data,

- The default target of our build is a list of docker containers, one for each service of the system plus the nginx container,

- At the root of the dependency graph lies our build containers: one for ghc + clojurescript and one for building javascript code. Those containers are only expected to change (and be built) when we upgrade our toolchain. They are somewhat expensive to build as they need to provide all the needed tools to build (and run) our system,

- On the server side, we use the

ghc-clojurecontainer to run a top-level build script that builds all services and the web UI. Given it takes ages to download and build all dependencies, then build all the various parts of the system, we tried to maximize reuse across builds: The build artifacts are exported as data containers and we link to the \(n-1\) build container in the \(n\) build run, - In order to minimize the size of our containers, we extract each service’s executable from the full build container and repack it into another container which contains a minimal runtime environment. We initially tried to do something like haskell-scratch but this did not work when our code needed to issue client-side HTTPS request: For some network and SSL reason the service fails to initialize properly. We resorted to use the standard busybox image, to which we add some prepackaged runtime libraries. This allows us to deploy containers with a “small” size: Our main application container weighs in at about 27MB and a typical service weighs 10MB. Note this has the additional benefit of drastically limiting the attack surface of the containers as they only contain the bare minimum to run our services and nothing else,

- Shake build also contains rules to run different class of tests: Unit/integration server-side tests, UI tests and end-to-end-tests (see below), and rules to clean build artifacts and docker containers.

Development Environment

Haskell

There has been various attempts at providing an IDE for Haskell: * leksah is an Eclipse-based Haskell IDE, * Haskell for Mac, * FPComplete used to provide some web-based environment.

Having used emacs for years, I feel comfortable with and besides there are actually benefits using a plain-text tool for coding when you are part of a distributed team: It allows you to easily setup a distributed pairing environment with minimal latency. Yet configuring a proper Haskell development environment in Emacs can be a challenging task, and it seems this is a moving target.

- Starting from Haskell-mode page is good idea as it is the base upon which one builds her own Emacs Haskell experience.

- Emacs haskell tutorial provides some more details on how to set things up,

- Chris Done’s Haskell config provides an easy to use full-blown configuration,

- I tried SHM a couple of times but could not get used to it, or could not make it work properly, or both… Might want to retry at some point in the future,

- this blog post is a bit older but I remember having gone through it and try to reproduce some of the proposed features

- This other post

- ghc-mod is useful but With cabal sandboxes and multiple projects it seems to be pretty unusable. I am also having a hard time making it work properly for test code: This requires different configurations and package dependencies are not properly picked up by ghc-mod. I need to investigate a bit more as I found this extension quite interesting,

- Some people at Capital Match have started to use spacemacs which seems to come with a correctly configured Haskell environment out of the box.

Here is my current .emacs content:

(eval-after-load "haskell-mode"

'(progn

(setq haskell-stylish-on-save t)

(setq haskell-tags-on-save t)

(setq haskell-process-type 'stack-ghci)

(setq haskell-process-args-stack-ghci '("--test"))

(define-key haskell-mode-map (kbd "C-,") 'haskell-move-nested-left)

(define-key haskell-mode-map (kbd "C-.") 'haskell-move-nested-right)

(define-key haskell-mode-map (kbd "C-c v c") 'haskell-cabal-visit-file)

(define-key haskell-mode-map (kbd "C-c v c") 'haskell-cabal-visit-file)

(define-key haskell-mode-map (kbd "C-c C-t") 'ghc-show-type)

(define-key haskell-mode-map (kbd "C-x C-d") nil)

(setq haskell-font-lock-symbols t)

;; Do this to get a variable in scope

(auto-complete-mode)

;; from http://pastebin.com/tJyyEBAS

(ac-define-source ghc-mod

'((depends ghc)

(candidates . (ghc-select-completion-symbol))

(symbol . "s")

(cache)))

(defun my-ac-haskell-mode ()

(setq ac-sources '(ac-source-words-in-same-mode-buffers

ac-source-dictionary

ac-source-ghc-mod)))

(add-hook 'haskell-mode-hook 'my-ac-haskell-mode)

(defun my-haskell-ac-init ()

(when (member (file-name-extension buffer-file-name) '("hs" "lhs"))

(auto-complete-mode t)

(setq ac-sources '(ac-source-words-in-same-mode-buffers

ac-source-dictionary

ac-source-ghc-mod))))

(add-hook 'find-file-hook 'my-haskell-ac-init)))

(add-hook 'haskell-mode-hook 'turn-on-haskell-decl-scan)

(add-hook 'haskell-mode-hook 'turn-on-haskell-indentation)

(add-hook 'haskell-mode-hook 'interactive-haskell-mode)

(add-hook 'haskell-interactive-mode-hook 'turn-on-comint-history)

(eval-after-load "which-func"

'(add-to-list 'which-func-modes 'haskell-mode))

(eval-after-load "haskell-cabal"

'(define-key haskell-cabal-mode-map (kbd "C-c C-c") 'haskell-compile))Thanks to discussions with Simon and Amar I am now using the REPL much more than I used to. My current workflow when working on Haskell code looks like:

- Load currently worked on file in interpreter using

C-c C-l: This starts an inferior-haskell which is configured to usestack ghci --testunder the hood, meaning all files including tests are in scope, - Code till it compiles properly and I can run a test,

- Make test pass in the REPL,

- When it’s OK, run full build, e.g.

stack testin the console. This might trigger some more changes downstream which I need to fix, - When all unit tests pass, commit and push to CI.

Clojurescript

The nice thing when using non-modern languages like Haskell and Clojure is that you only need to be able to edit text files to develop software, hence the choice of Emacs to develop both is kind of obvious. There is very good support for Clojure in emacs through nrepl and Cider but it seems having the same level of support for Clojurescript is still challenging.

- When developping UI ClojureScript code, I mostly use figwheel which provides interactive reloading of code in the browser. One needs to start figwheel through

lein figwheelwhich provides a REPL, then load the UI in a browser: The UI connects to the figwheel server which notifies it of code changes that trigger reload of the page, - For (mostly) non-UI code, I tend to favour TDD and use “autotesting” build: Changes in code trigger recompilation and run of all unit tests using the same configuration than batch run,

- paredit-mode provides a structured way to edit LISP-like code: It automatically balances parens, brackets or double-quotes and provides dozens of shortcuts to manipulate the syntax tree ensuring syntactically correct transformations. I tend to use it as much as possible but sometimes find it cumbersome,

- What I miss most when developing ClojureScript is a way to identify and navigate across symbols: I could not find an easy way to have some symbols index, something which is provided for Haskell through simple tags support. I am pretty sure there is something out there…

Devbox

I already discussed in a previous blog post how we managed to do pair programming with a distributed team. One of the virtual machines we configured was our devbox which we used to do remote pairing and run experiments.

- The initial configuration was done in the VM. It was pretty complex, requiring setting up full Haskell and ClojureScript toolchain, correct Emacs configuration which means installing and configuring emacs packages in scripts, setting user authentications…

- It worked quite well however, except for the time to spin up a box from scratch. We were able to develop our software using the same tools we had on our laptops, except the fancy windowing UI: Emacs works exactly in the same way in a (proper) terminal and in a Mac OS X Window, once you correctly configuring key mappings for tmux and emacs over ssh,

- At some point we turned to a container-based configuration with a fat container providing full development environment, including an X server for UI testing. Setting up the VM was much simpler as it only required installing docker but the development image was pretty large (about 4GB) and this meant long download time when pulling the docker image from scratch. This environment provided a full-blown X server which means we could log into it through VNC. However, we lost interactivity of pairing as it was not possible to share connection to X server which actually means it was pretty much useless,

- We reverted back to configuring the VM itself but this time we used images snapshot to be able to restore the box quickly,

- We also pushed emacs configuration to a shared git repository which is pulled when configuring the machine, something we should have done earlier of course.

Discussion

Build process

In retrospect I think the biggest issue we faced while developing the platform and working on the dev and prod infrastructure was fighting back increase in build time as we were adding new features and services. Building a deployable container from scratch, including creation of the build machine, configuration of build tools, creation of the needed containers, download and build of dependencies, testing, packaging would take about 2 hours. Here is the breakdown of time for some of the build stages according to the CI:

| Test | Mean |

|---|---|

| IntegrationTest | 7m51s |

| EndToEndTest | 7m05s |

| Compile | 6m05s |

| ParallelDeploy | 1m12s |

| UITest | 53.46s |

Even if tests are run in parallel, this means it takes more than 10 minutes to get to the point where we can deploy code. Actually, CI tells us our mean time to deployable is about 30 minutes, which is clearly an issue we need to tackle. To reduce build time there is no better way than splitting the system into smaller chunks, something the team has been working on for a few months now and is paying off at least by ensuring we can add feature without increasing build time! The next step would be to split the core application which currently contains more than 80 files into more services and components.

On the positive side:

- Shake provides a somewhat more robust and clearer make, removing cryptic syntax and reliance on shell scripts. All the build is concentrated in a single Haskell source file that requires few dependencies to be built,

- Haskell build tooling has been steadily improving in last couple of years especially since stack has taken a prominent position. Stack does not remove dependency on cabal but it actually reduces it what cabal does best: Providing a simple, descriptive configuration for building single packages ; and provides a definitely better experience regarding dependency management, build reproducibility and managing multiple build configuration,

- I am less happy with the ClojureScript and Javascript parts, probably because I am much less familiar with them, hence I won’t enter trolling mode,

- Packaging build environments with docker greatly reduces development friction: Issues can be reproduced very easily against a reference environment. Developer’s freedom is not comprised: Everyone is free to configure her own environment with CI acting as final gatekeeper while making troubleshooting somewhat easy (grab image and run it locally to reproduce problems),

- Using containers also makes onboarding of new developers somewhat easier: They can focus on a single part of the system (e.g. UI) and rely on the containers to run a consistent environment locally.

Development Environment

The single feature I miss from my former Java development environment is refactoring: The ability to safely rename, move, extract code fragments with a couple key strokes across the whole code base lowers the practical and psychological barrier to improve your code now. GHC (esp. with -Wall -Werror flags on) catches of course a whole lot more errors than Javac or gcc but the process of fixing compiler errors after some refactoring of a deeply nested core function is time consuming. On the other hand the lack of global refactoring capabilities is a strong incentive to modularize and encapsulate your code in small packages which can be compiled and even deployed independently.

To be continued…