Using agile in a startup

This post is a follow-up to my previous post on designing an application in Haskell and part of a series of post I intend to write that reflect on my experience as CTO of Haskell-based startup. Whereas the previous post was very technical, focusing on what we built, this one focuses on how we built it: Processes, methods and tools we used, how the team was built and how it interacts on a daily basis, which problems we encountered and how we solved them (or not)… As before I have tried to be as honest as possible, highlighting both what worked and what did not work so well.

Coming from an Agile background it is no surprise that I consciously tried to reuse the knowledge and tools I knew from previous implementations of Scrum, eXtreme Programming or Kanban. One of the lesson learned during the past year is that Agile needs some serious overhauling to be applied within a startup setting, even more so when the team is distributed. In the conclusion I try to draw on this experience to hint at some trails I would like to explore in the future.

A Bit of Context

I started working on Capital Match at the end of August 2014. The first commit in the git repository of the application is dated on Wednesday, 20th of August 2014. I worked in the background for a couple of months, mostly to setup the infrastructure, flex my muscles on Haskell, explore the business domain space.

I met physically my co-founder in October. At that time I was still working alone but I already had a working solution that was deployed and “usable”, for some definition of usable. Willem van den Ende joined me to develop the application to production stage at the end of October and brought with him lot of XP and DevOps experience. We were joined by another developer at the beginning of March but this employment lasted only a month.

We went live on the 20th of March, one month after the initial target set in December. The tech team is now 4 people, including me, all of which are mainly developers. We do not have a dedicated operations team and the tech team is responsible for both developing new features and maintaining the application in good operational conditions.

Planning

Project Planning

We started using taiga.io from November to plan the go-live, first without then with spring planning. It was a good thing to explain to non-tech people we can deliver so much in a period. We quickly settled on 1 week sprints and it took us a while to get to some form of regularity and cadence, never really get to smooth release and meaningful Story Points values. A month or so after go-live we switched to a kanban style process which is not really well supported by taiga.

It seems people are having a hard time understanding SP, and when they understand they start trying to game it and discuss evaluations. It fairly quickly gets back to “when will it be done?” and “can’t we really do it faster?” and “what if we did XX?” questions… Smart people used to work with figures are prone to get to the conclusion figures are acutally measuring output and value and then we will use those figures to measure success.

We dropped formal estimates, even before golive: what’s done is done, when it is not done it is not done. In order to cope with unrealistic expectations and requirements we strived hard to make everything visible, deploy very quickly and allow people to test easily, work in baby steps… in other words reduce the length of the feedback loop. We don’t provide estimates anymore, and people don’t ask for them, except in very broad terms for high-level features which we (I) estimate as S/M/L or some combination thereof.

People also had a hard time using taiga (and I am not sure it would have been better with any other tool…): Response is a bit slow, most of the things don’t make sense for them, they don’t follow really tickets and comments on them… nor do they care much about tracking SPs progress.

So we finally switched to using plain trello:

- Its interface is very intuitive to pick, and most people already have used it at some previous point,

- The user interface is super-fast and reactive,

- It provides nearly all the features we need, except swimlanes but we use tags instead,

- It is available on a wide variety of platforms, e.g. as a mobile app.

We currently use 2 boards:

- Software Development board is used for day-to-day work. It contains baby step features and bugs, and has very simple workflow:

- To prioritize is used for brain dumping features, and we try to clean up at frequent interval,

- To Do is for actual stuff to do. We strive to keep those items fine-grained, e.g. no more than 1-2 day of work,

- Doing says it all. We try to minimize Work-in-progress by ensuring people do not work in parallel on more than one feature. It is at this stage that tickets are assigned and not before,

- Ready for testing means ticket has passed CI (more on this later) and is ready to be tested on staging platform with non-production data. Once or twice a day we send an email notifying people of whatever is available to test on staging platform,

- Deployed means feature has been deployed to production platform. Just like for staging, we send an email to involved people every time we deploy new feature to production.

- Product roadmap board is used for larger scale planning. It contains 3-months columns and coarse grained features estimated using S/M/L t-shirt sizes. There is one Ongoing column which contains features we are currently working on. It is mostly used as a reminder of “large” things we want/need to do.

Product Development

I wrote a “walking skeleton” in a month or so, starting from initial idea, while my partner was sorting out the business side of things and trying to find seed investors in the project. This walking skeleton was, well, very skeletal, being able to handle only very basic scenario: register borrower/investor, create new simple, loan, commit funding to loan then accept loan.

When go live started to come close, business people got scared and wanted to go into command and control mode, and wanted to go into the following process:

- They designed very detailed “screens” in Excel with lot of complex business rules, strict wordings… covering the complete scope of the application as we initially discussed it,

- Devs would work one screen at a time and complete it before going to the next,

- Then they would tests what devs produce,

- Then bugs would be notified and needed to be fixed,till business is happy

- In short, we were reinventing Waterfall without the good parts (e.g. formal V&V)

I used the initial provided design documet to slice everything into small stories with estimates and put that into Taiga, then we started working on it following the aforementioned process. After 1-2 weeks it became obvious to everybody we would not be able to deliver everything that has been designed in excruciating details, because we simply could not code fast enough. Something like about 40-50% only of the designed features were actually shipped on go-live. Hence we reverted to priority-based scheduling and Dimensional planning with one week sprints and a target release date.

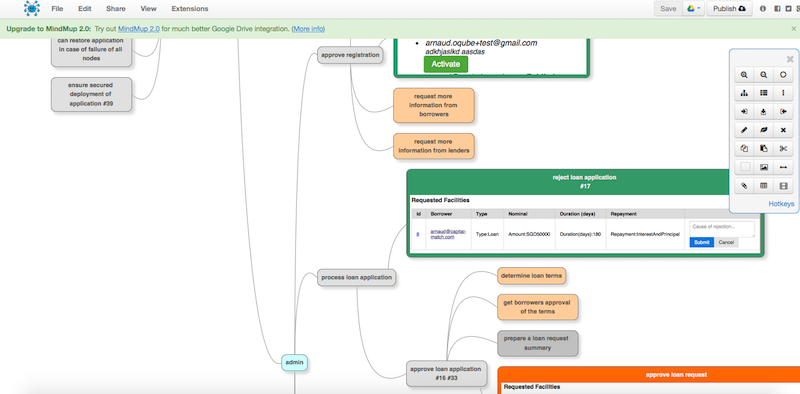

At some early stage I tried to use Story mapping, maintaining a map of the software’s features using MindMup a hosted mind-mapping application:

The idea was that we would represent the whole process in a map, distinguishing manual/automated parts and filling the leaves with actually available features. However this did not gel and people never get accustomed to use that representation of the software, so I quickly stopped maintaining it.

Programming Practices

Pair Programming

We started doing remote pairing with Willem and we still try to do it on a regular basis. Remote pairing works really fine if the network has no hiccup. We have the following simple setting:

- We setup a remote VM containing the development environment (compilers, source code) and accessible only to the team. Configuration of this VM is kept versioned in our code repository hence it follows the evolution of the code itself which may require over time different dependencies, different compilers… To be able to quickly setup a VM, we use a snapshot instead of full-blown configuration

- People connect on the VM using with ssh and tmux1, and we use console-based emacs for hacking. OF course this is possible because we are using languages and tools that do not need a complex visual IDE to work2,

- We use hangout for voice + video. Small tip, thanks to Emmanuel Gaillot: Set your terminal to be slightly transparent so that you can see the remote persons behind the code!

I really like pair programming but I found its remote version is more exhausting than its face to face counterpart. It requires more focus and engagement because it is very easy to get distracted as your partner is not there to snoop over your shoulder and see you are actually browsing your emails or twitter. And the lower fidelity communication requires even more focus. However we found that timezone differences forced us to make something like Deferred Pairing: I start some work in France, using slack as a stream of consciousness, pushing code to github repository, then I go to sleep. In the middle of the night someone in Asia picks up where I left code and continue working on it till we manage to have some time overlap. Then we can pair for a couple of hours if needed, and restart the whole cycle.

Development Automation

Continuous Integration is core practice of XP and we embraced it fully from the onset of the project in the form of continous deployment: Each code change’s integration in the existing codebase is checked as soon as the code is published to be available for the whole team to use. Continuous should of course be understood in the mathematical sense, e.g. opposite of discrete: You are able to deploy at any point in time, not at certain gateways or releases milestones. I plan to provide more details in another blog post but practically speaking this means:

- People push to a “central” git repository located on a CI server. Note this repository is central only by virtue of being on the CI server and we could deploy other servers and “central” repositories at will. There is nothing special and we try to keep using git in a distributed way,

- This triggers a job on the CI server which, among other things, runs automated tests (more on this later) and deploy an instance of the application for testing, and pushes the same instance to a central repository for deployment to production.

This implies managing infrastructure, e.g. VMs, containers, processes and would not be possible without strong automation: Infrastructure as Code and DevOps everywhere, the slogan is: Automate all the things!

- We can rebuild all our infrastructure from a couple of git repositories

- Note: CI server is itself versioned and deployable

- VM deployments is not fully automated yet but is scripted

- Configuraiton management is versionned and handled in Haskell too

Continuous Integration is really our most important tool for maintaining cohesion in the team and integrity of the software: Any commit pushed to CI triggers whole chain of build down to the point we obtain a deployable application container

Test Driven Development

I have already written on TDD and how much I loved it: To me TDD is THE core practice of XP and its main contribution to the advance of software development. Even in a startup setting I don’t think we made a lot of compromise on writing tests, but the amount of tests that need to be written in a strongly-typed language like Haskell is less than what you would need to write in Ruby or even Java.

Our automated tests are currently divided into 4 types:

- Property based tests, expressing pure code’s properties like symmetry of read/write, description of processes, computations… There aren’t that many properties in our code, mostly I think because our domain is rather simple and not easily amenable to compact formulation of properties: There is no point in expressing a property in a way that is as complicated as the code it is supposed to specify,

- Integration tests check our code within the context of I/O, mostly through its REST interface but sometimes only using basic I/O or imperative code. This is where we catch most of our errors because it is very easy to make a mistake when interacting with the outside world, whereas the compiler and explicit types help a lot in catching internal programming mistakes,

- User Interface tests are actually unit tests for the UI code which is written in Clojurescript. These are the least developed part of our test stack which is a pity given the dynamic nature of the language we use and the amount of UI code we have, but we try to remove logic from UI as much as possible and most of the issues we have at this level are actually user interactions problems which can more quickly be caught through actually using the interface,

- End-to-End tests like their name implies tests the application at the highest-level using Selenium to drive a browser to interact with the application like a human being would do. We have about 20 tests in this category and we try to keep that number low as obviously they are the more costly ones to run. However they are really invaluable in catching complex integration issues.

Team

On Being Remote

Working remotely has been an integral part of the organization since the beginning. We are 6-7 hours apart, e.g. it is afternoon in Singapore when I wake up. This means we have about 3-4 hours of overlap, but we span 16-17 hours of wall clock time. Here are some features that are entailed by being remote:

- This removes the need for a dedicated support/ops team, at least as long as we are smallish (see above notes about automation)

- We do our stand-up meeting at 9am or 10am Paris Time, acts as a sync point,

- We use overlap time for discussing stuff, pairing, solving design or hard technical problems. Hangout works ok but it would probably be better with dedicated software e.g. gotomeeting or equivalent)

- We found that timezone differences are actually great for catching date/time related bugs!

- We use Slack a lot. We could use IRC of course but it would require some more infrastructure and it is not

as friendly to non tech-savvy persons:

- We use ut to chat within the team and discuss technical stuff, post screnshots, code examples, design ideas…

- We use it as a stream of consciousness endpoint: I dump what I am doing, jot down ideas, humours, feelings… When people wake up in the morning they have a trace of what I have done apart from the actual code/builds I produced and what I have been thinking of

- We also use it as an endpoint for some important monitoring information, e.g. when something is pushed to central git repository or when state of a server changes.

There is a great post about Remote First culture: http://zachholman.com/posts/remote-first/ which you should read, along with 37 Signal’s Remote. They both emphasizes the fact that working remotely works if and only if the whole organisation is built around this premise. Think as a counter-example organisations that have a handful of offices which need to work distributedly. Distribution was an afterthought, something that came up as a constraint because of mergers, and no amount of tooling can make that kind of culture work.

Remote work can help reduce stress, especially in startups: Being remote means you can simply remove pressure from business people when it becomes too heavy. It can also help minimizes personality clash, cool down interactions. Being face-to-face increases cues and hints about the other person’s feelings but is also a great way to generate stress and emotions. The counterparty is trust: People at the other side of the world trust you to do what needs to be done

Hiring

The team is currently very small but hiring has been and will stay a team matter. Because we use a niche technology our recruitment is necessarily international and we must be prepared to recruit and work remotely, and actually I was recruited as co-founder remotely…

Our hiring process is currently quite simple:

- Initial interview with me and/or another dev where I try to assess current skill level of candidate. Usually ask questions related to basic XP practices like TDD

- 2 hours pairing (or tripling) session using our remote dev environment: We usually tackle the GildedRoseKata in Haskell, or if candidate is not comfortable enough in his favourite language (Javascript, Java…)

- Interview with CEO and negotiations…

- Here we go!

Applying agile principles to hiring means that we are ready to experiment for a week or a month, reflect and improve, and possibly stop early (this occured already once). Doing this remotely also means more flexibility and more risks:

- If the person you hire wants to cheat, e.g. steal your code, she can do so quite easily,

- Developers are freelance in their country, which means they can stop at any time,

- Hence finally there is an incentive for Capital Match to keep people happy and motivated.

Hiring is one of those (numerous) areas where I see a lot of improvements and where being remote is a game changer.

Theorizing

Lessons learnt are most interesting if you can leverage them into some form of theoretical knowledge that can be turned into useful guidelines for future decisions. This section tries to extract some possibly useful insights and generalisations from this limited experience, which I can summarize in three points:

- Treating software as development projects alone is a fallacy that leads to costly errors,

- Technology matters,

- Our software is part of a system that has different requirements at different moments in time.

The Software Development Project Fallacy

There is not a dearth of software development project management methods, whether Agile or not: Kanban, Scrum, RUP, Waterfall, V, W, Design Controls… And symetrically there are quite a few methods targeted at managing operations and support in IT, like ITIL, although I am much less familiar with those. The fact is they are all inspired by the logic of manufactured goods design and production where:

- The good undertakes a series of transformations, from design to production, up to the point it is ready for consumption by the “public”,

- Where it falls into the hands of another group of people which is responsible for maintenance or end-users support.

If we focus on Scrum alone, we find the core artifact to be the sprint and a number of sprints ultimately leading to a release. But sprints, and for that matter any form of time-constrained activity, are inherently exhausting and ultimately unsustainable, hence the mutiplications of hardening sprints, release sprints, sprint 0… which are all attempts to depart from the sprint/release straightjacket. What Scrum and even XP which is dearer to my heart misses is the Operations part of a system

Scrum is a management and control process that cuts through complexity to focus on building software that meets business needs. Management and teams are able to get their hands around the requirements and technologies, never let go, and deliver working software, incrementally and empirically.

Scrum itself is a simple framework for effective team collaboration on complex software projects.

The way of thinking this methods promote is inherently constrained by a time-bound horizon: The moment the product will be considered “finished” and leave the organisation that produced it, hence the emphasis of the release. Lets remember that Deliver3 also means give birth and bears with it the idea that something we have been fostering for months is freed from our control, which also suggests we are freeing ourselves of it. Deliver’s substantive is deliverance… The release becomes the horizon of the team and with it comes relief, and then we move on to something else.

What I have learnt over the years but even more so over the past months working on this project is the importance of evaluating your capability to deliver features against your capability to maintain your software and make it able to sustain more change in the future. Viewing software systems solely under the angle of projects leads to a bias, from all persons involved, towards delivering more under time pressure which is the biggest source of errors. When your horizon is time constrained you cannot pay enough attention to the small warnings that will lead to big failures.

Technology matters

“The technology, stupid.”

liberally adapted from James Carville

Obviously a lot of the things we do are made possible thanks to technology:

- Being distributed is now workable because there are quite a few affordable tools out there that make this style of working possible for small teams: Google Hangouts, Skype, Slack/IRC, mails of course, Git, SSH, Cloud providers, Docker, Linux are all key ingredients to make our distributed workplace possible4,

- Developing our business as an online platform is also a key factor in enabling both an iterative and inherently agile style of software but also in the availability of tools and systems. It is much harder to develop an embedded controller’s system in a remote way because your software is physically tied to something concrete,

- The free and/or open-source movement has popularised geographically distributed teams and flat hierarchies for developing even very large pieces of software.

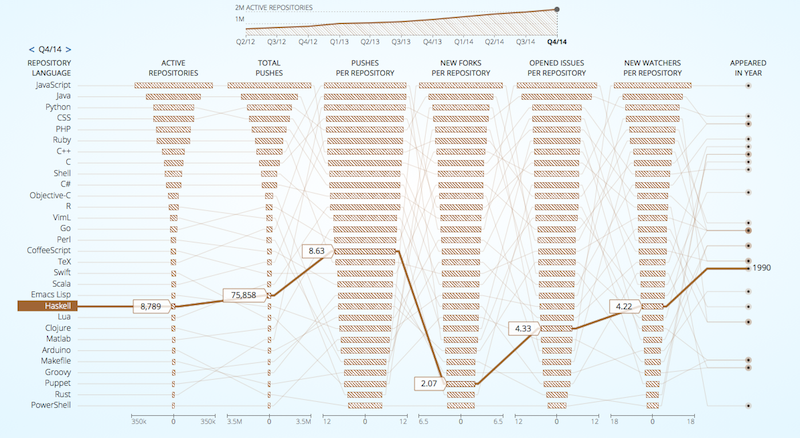

But I do think that our particular technology stack (e.g. Haskell) choice has a deep impact in enabling this distributed agile style of working:

- Haskell is (still) a niche language for at least two reasons: Because of its paradigm which is very different from maintstream languages

and platforms, and because of its history which ties it to academic and esoteric PLT research more than to the production of

mundane web applications,

- Due to its niche nature, it attracts programmers that either want to distinguish themselves and/or are inherently attracted by the different, not to say the bizarre… This is often the kind of people that are ready to make some extra efforts to keep on working with such a language, including working with shifted hours, moving to a foreign country, learning new tools and processes…

- On a more technical side, this particular choice allows us to work mostly through lightweight text-based tools, e.g. terminals, text editors, SSH… something which is invaluable when you have to communicate over 10000 kilometers and flacky Internet.

Technology is not neutral. As explained by Bruno Latour, technology is embodied into technical beings whose needs must be adressed in specific ways and with whom we need to interact in specific ways. Technology shapes our worldview and the way we work in a lot of different and sometimes surprising ways. But it is always worthwhile to think about it beforehand…

From Project to System

My experience suggests a different approach which does not reject the benefits of iterative software development but makes it part of a bigger process which also encompasses the need for periods of reflection and calm. We should acknowledge the duality (at least) in our processes:

- Period I: Moments of intense activity, which might be due to deadlines, objectives, production incidents to solve, security issues…

- Period II: Moments of routine activity where team can reflect, define processes and procedures, refine things, document…

Agile methods are good at channelling the intensity of period I through a simple process but they are much less appropriate for period II which is mostly characterized by the absence of definite goal(s). This explains the rise of “hybrid” approaches and the success of Kanban which offers a much more appropriate framework to handle period II work (and conversely is not very well suited to period I…). This also explains the moderate success (at best) Agile methods have with operations or highly regulated settings.

There is a lot to get inspired from the way Highly Reliable Organisations work and the numerous research studies that have been written about those organisations. I was also personally heavily influenced by “Les décisions absurdes” which describes the mechanics of group thinking and how they can lead to catastrophic failures. HRO studies show that those organisations which must be reliable actually acknowledge the existence of those two modes of operations. The best such organisations know how to take advantage of routine mode (what I call Period II) to become better when the need arises to go into intense mode or Period I.

Think of those analogies:

- In sport, athletes do not spend 100% of their time competing, and actually competition accounts for a small fraction of their worktime, most of it is dedicated to training, learning, improving, reflecting on past competitions,

- Musicians and other performers do the same: A lot of time training and practicing, small fraction of their time on stage,

- Soldiers and military are an even better analogy because period of conflicts can last for an extended period of time and even then, army takes care of rotating personel, replacing people on the front with fresh troops on a regular basis.

The content of this post was used to present a session at Agile Tour Nantes 2015: Thanks to the organisers for having accepted that talk.

Thanks to Anne Caron-Perlon for her very helpful comments and remarks.

Thanks to Capital Match Team for those exciting 2 years.

It seems that tmate provides even better support for that at the expense of having to setup a centralised server for people to log in.↩︎

Looks like the smart people at /ut7 have given a name to this: They call it La bassine and apparently this has been developed as part of work on project for Deliverous↩︎

This comes from the French Délivrer which can be translated to get rid of, relieve, set free↩︎

Back in the 90s or even early 2000s you would have to be either a large corporation, a university or deep hacker group to be able to work distributedly in real time↩︎