First Steps with MirageOS

This post is a follow-up to the session I gave at Devoxx France on MirageOS. It provides detailed instructions on how to setup a development environment to be able to:

- Build locally Mirage projects and generate native binaries with

--unixconfiguration flag, - Install and configure a VirtualBox VM that runs Xen Hypervisor,

- Build Xen-enabled Mirage unikernels on this VM.

References

Those points are already covered in other documentation material available here and there on the web and I mainly did some synthesis from a newbie perspective. Here is a list of resources that were helpful in making this post:

- Official MirageOS Wiki which contains various tutorials,

- mirage-www, the self-hosted website,

- Magnus Skjegstad blog post which mostly covers point 2. above, and another post which covers more advanced stuff,

- Doing nothing in Mirage, an older post on basic configuration,

- An account on recent Solo5 development to run Mirage on Qemu,

- Another getting started blog post

- Some random pages on Xen configuration:

- Accessing the Internet from domU kernels,

- Networking in Xen, not for the faint of heart,

- Related work for HaLVM, the unikernel system in Haskell.

A Naive Authentication Service

Goal

The goal of this post is to build a simple HTTP service that can authenticate users based on their password. This service’s specification is simple, not to say simplistic and naive:

- It maintains a key/value store from user names to passwords (we do not care about encryption here but of course they should be),

- It receives

GETHTTP requests on port 80 and expects two parameters in the query part: Auserstring and apasswordstring, - If the given password for given user matches stored password, it responds with

200 OK, - In all other cases it should return

401 UNAUTHORIZED.

To build this service we need to:

- Run a HTTP Server: I will use ocaml-cohttp which is built specifically to be run within MirageOS applications,

- Store data in some key/value store: MirageOS provides

kv_rowhich is an abstract key/value store which can be backed in code or in a FAT-formatted disk image.

Server Code

The server code resides in a unikernel.ml file. I am not at all familiar with OCaml so my code is probably not really

idiomatic. Learning OCaml is one of the reasons I became interested in MirageOS in the first place !

We first need some usual incantations to “import” names, e.g. opening modules in OCaml:

open String

open Lwt

open Lwt.Infix

open V1_LWT

open PrintfThe string_of_stream function is adapted from the basic kv_ro example provided in mirage-skeleton. Its name is pretty explicit…

let string_of_stream stream =

let s = List.map Cstruct.to_string stream in

return (String.concat "" s)The main module is parameterized by 3 signatures which are provided by MirageOS according to the configuration given at

build-time. Here we have 3 modules: The console for outputting some logs, the Key/Value store and conduit which provides

network connectivity:

module Main (C:CONSOLE) (K: KV_RO) (CON:Conduit_mirage.S) = structWe build a new module by passing underlying connection manager to our HTTP server implementation then we can define our start

entry point:

module H = Cohttp_mirage.Server(Conduit_mirage.Flow)

let start console k conduit =We first define the function that will check the database for matching username/password pair, given an access request. The main

thing to note here is that reading from the store happens within the context of so-called light-weight threads or Lwt which is

the basic Mirage cooperative thread execution model. Potentially blocking operations expect a continuation that will be passed the

result of the operation.

let check_pwd u p =

K.read k u 0 4096 >>= fun readpwd ->

match readpwd with

| `Ok pwds ->

string_of_stream pwds >>= fun pwd ->

return $ compare (trim pwd) p == 0

| _ -> return false

in Then comes the meat of the server, the http_callback function that will be called by cohttp upon everyrequest. We extract

interesting parts of the request’s URI then check whether or not the username/password pair matches, and finally return a response.

let http_callback _conn_id req _body =

let uri = Cohttp.Request.uri req in

let path = Uri.path uri in

let user = Uri.get_query_param uri "user" in

let pwd = Uri.get_query_param uri "password" in

match (user,pwd) with

| (Some u, Some p) ->

check_pwd u p >>= fun chk ->

if chk

then H.respond_string ~status:`OK ~body:(sprintf "hello %s!\n" u) ()

else H.respond_string ~status:`Unauthorized ~body:"Invalid login\n" ()

| _ ->

H.respond_string ~status:`Unauthorized ~body:"No user given\n" ()

inIt remains to start the ball rolling by creating the HTTP server and listening on some port, using underlying CONduit module

implementation:

let spec = H.make ~callback:http_callback () in

CON.listen conduit (`TCP 8088) (H.listen spec)

endThe single most important thing to note here is that this code is pretty much system-agnostic: There is no dependency on a

particular low-level runtime infrastructure and the same code can be run either as a native binary on Unix or packaged as unikernel

on Xen (or QEMU). Implementation details are hidden behind the signatures, e.g. interfaces, that parameterize the Main module and

whose instances are passed to the start function.

Configuring Mirage

The second important file one has to write for a MirageOS application is the config.ml file which is used by mirage tool to

generate the needed boilerplate to run the actual code.

After the incantation to access Mirage module’s content, we define our first component that will be melded in our

application. This one is a simple generic key/value store whose content will be built from the data/ directory. In Unix mode

requests for some key will be matched to the content of the data/ directory, whereas in Xen mode we will need to pack that data

inside a block device and mount that device in the built kernel

open Mirage

let auth_data = generic_kv_ro "data"Our second component is the HTTP server. We can see here our configuration depends on the underlying platform. Note that the

generic_stackv4 provides IPv4 implementation for both Unix and Xen and strictly speaking we could get rid of the if_impl

construct. It is also possible to use a direct_stackv4_with_default_ipv4 implementation on Xen: This will assign a static IP to

the kernel which can be changed when configuring mirage.

let server =

let network =

if_impl Key.is_xen

(generic_stackv4 default_console tap0)

(socket_stackv4 default_console [Ipaddr.V4.any]) in

conduit_direct networkThe handler function defines the general structure of our service and adds some libraries and packages to be imported by

mirage. Then we can finally register our auth_service passing it the result of invoking handler with actual implementation of the

modules it requires.

let handler =

let libraries = ["mirage-http"] in

let packages = ["mirage-http"] in

foreign

~libraries ~packages

"Unikernel.Main" (console @-> kv_ro @-> conduit @-> job)

let () =

register "auth_service" [handler $ default_console $ auth_data $ server]I must confessh this part is still a bit mysterious to me…

Building on Unix

We will assume mirage is installed according to the instructions. At the time of this writing, we use:

$ opam --version

1.2.2

$ ocamlc -version

4.02.3

$ mirage --version

2.8.0We can first try to build and run our service on Unix, e.g. locally. We first need to populate a data/ directory with some files

representing usernames and add a password inside each file. Then we can configure Mirage, build the executable using the generated

Makefile and run it.

$ mirage configure -vv --unix

...

$ make

$ ./mir-auth_service

Manager: connect

Manager: configuringIn another console, we can test that our authentication service works correctly:

$ curl -v http://localhost:8088/foo/bar?user=john\&password=password

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< content-length: 12

<

hello john!

$ curl -v http://localhost:8088/foo/bar?user=john\&password=passwor

< HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

< content-length: 14

<

Invalid loginSo far, so good! We are now ready to test our unikernel for “real”, e.g. to configure a VM running Xen in VirtualBox…

Configuring a Xen VM on Virtualbox

Note: This has only been tested on the Ubuntu 14.04 box

Fortunately for us, all the grunt work has already been done in the mirage-vagrant-vms which I simply forked and extended to add the following features:

- Install the latest Official version of ocaml toolchain and mirage environment,

- Configure a host-only network for the VM,

- Configure bridge, dnsmasq and IP forwarding in the VM to be used by Xen domU kernels.

Networking

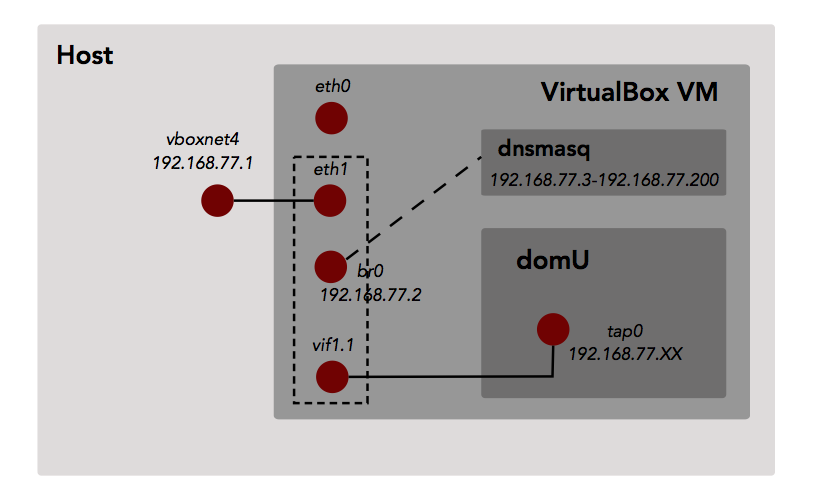

The part I had most difficulties with is of course the networking part. We want the domU virtual machines running on top of Xen hypervisor inside the VirtualBox VM to be visible from our host. The following picture tries to render my understanding of the network topology and configuration we want to achieve (actual IPs/MACs may of course differ).

The VirtualBox engine exposes the host-only interface to the host as vboxnet4 with a pre-configured IP (e.g. IP is set in Vagrantfile as part of definition of host-only network). This interface is linked

to the eth1 “physical interface” inside the VM and part of the same ethernet network. We create a br0 interface which is a bridge: An interface that connects two or more interfaces by routing the packets to/from each of the bridged interfaces. In this case it connects the host-only interface

(eth1) and the the virtual interfaces created for each domU kernel, in this case vif1.1. The latter is pair of a pair of virtual interfaces created by underlying hypervisor when the domU kernel boots up, the other member of the pair being the tap0 interface on the domU side. Each packet going through either interface is made available to the other interface.

Another important is configuring and activating dnsmasq to ensure domU kernels will be able to get an IP address using DHCP. Here we configure it to be attached to br0 interface - our bridge - and to serve IPs from 192.168.77.3 to 192.168.77.200.

Last but not least, one must not forget to enable promiscuous mode on the host-only NIC created for the VM: I spent a couple hours trying to understand why my packets could not reach the unikernel although I could see ARP frames being exchanged…

Building MirageOS kernel on Xen-enabled VM

We are now ready to configure, build and run our unikernel on Xen VM. We assume code has been somehow uploaded to the VM:

$ mirage configure --xen -vv --net direct --dhcp true --tls false --network=0

...

$ makeThis creates a bunch of new files in the project’s directory, the most important one being auth_service.xl:

# Generated by auth_service (Wed, 20 Apr 2016 13:53:27 GMT).

name = 'auth_service'

kernel = '/Users/arnaud/projects/unikernel/auth-service/mir-auth_service.xen'

builder = 'linux'

memory = 256

on_crash = 'preserve'

disk = [ 'format=raw, vdev=xvdb, access=rw, target=/Users/arnaud/projects/unikernel/auth-service/tar_block1.img', 'format=raw, vdev=xvdc, access=rw, target=/Users/arnaud/projects/unikernel/auth-service/fat_block1.img' ]

# if your system uses openvswitch then either edit /etc/xen/xl.conf and set

# vif.default.script="vif-openvswitch"

# or add "script=vif-openvswitch," before the "bridge=" below:

vif = [ ]This is the descriptor that is passed to the Xen launcher to start the unikernel. We must also not forget to build the disk image that will be loaded in our unikernel and exposed to our program as a key/value store:

$ ./make-fat_block1-image.sh

$ sudo xl -v create -c auth_service.xlThe -v option asks xl to be verbose and the -c attaches a console to the launched kernel.

This does not work out of the box and I needed to manually edit the generated files to fix a couple of minor issues:

- The

disksection ofauth_service.xlcontains 2 disks but we only generate one of them, thefat_block1.img: Thetar_block1.imgmust be removed from the list, - The file

auth_service.xealso contains some descriptor for the same image, which needs to be also removed, - The

vif = []part should also be replaced byvif = [ "bridge=br0" ]to ensure network device for unikernel is attached to the bridge and can actually be assigned an IP through dnsmasq, memory = 256is also way too much: Replace withmemory = 32which should be enough (16 does not work…),- There is a slight error in the

make-fat_block1-image.sh: The block size used is made equal to the total size of the files to include in the image, which does not seem to make much sense. I set it to be 32Kb.

With this modifications one should expect to see something like the following being printed to the console:

MirageOS booting...

Initialising timer interface

Initialising console ... done.

getenv(OCAMLRUNPARAM) -> null

getenv(CAMLRUNPARAM) -> null

getenv(PATH) -> null

Unsupported function lseek called in Mini-OS kernel

Unsupported function lseek called in Mini-OS kernel

Unsupported function lseek called in Mini-OS kernel

getenv(OCAMLRUNPARAM) -> null

getenv(CAMLRUNPARAM) -> null

getenv(TMPDIR) -> null

getenv(TEMP) -> null

Netif: add resume hook

Netif.connect 0

Netfront.create: id=0 domid=0

sg:true gso_tcpv4:true rx_copy:true rx_flip:false smart_poll:false

MAC: 00:16:3e:2e:c2:ce

Attempt to open(/dev/urandom)!

Unsupported function getpid called in Mini-OS kernel

Unsupported function getppid called in Mini-OS kernel

Manager: connect

Manager: configuring

DHCP: start discovery

Sending DHCP broadcast (length 552)

DHCP response:

input ciaddr 0.0.0.0 yiaddr 192.168.77.157

siaddr 192.168.77.2 giaddr 0.0.0.0

chaddr 00163e2ec2ce00000000000000000000 sname file

DHCP: offer received: 192.168.77.157

DHCP options: Offer : DNS servers(192.168.77.2), Routers(192.168.77.2), Broadcast(192.168.77.255), Subnet mask(255.255.255.0), Unknown(59[4]), Unknown(58[4]), Lease time(3600), Server identifer(192.168.77.2)

Sending DHCP broadcast (length 552)

DHCP response:

input ciaddr 0.0.0.0 yiaddr 192.168.77.157

siaddr 192.168.77.2 giaddr 0.0.0.0

chaddr 00163e2ec2ce00000000000000000000 sname file

DHCP: offer received

IPv4: 192.168.77.157

Netmask: 255.255.255.0

Gateways: [192.168.77.2]

ARP: sending gratuitous from 192.168.77.157

DHCP offer received and bound to 192.168.77.157 nm 255.255.255.0 gw [192.168.77.2]

Manager: configuration doneAnd if now query our service from the host, it should reply:

$ curl -v http://192.168.77.157:8088/foo/bar?user=john\&password=password

* Trying 192.168.77.157...

* Connected to 192.168.77.157 (192.168.77.157) port 8088 (#0)

> GET /foo/bar?user=john&password=password HTTP/1.1

> Host: 192.168.77.157:8088

> User-Agent: curl/7.43.0

> Accept: */*

>

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< content-length: 12

<

hello john!

* Connection #0 to host 192.168.77.157 left intactWith the corresponding trace on the server side being:

ARP responding to: who-has 192.168.77.157?

ARP: transmitting probe -> 192.168.77.1

ARP: updating 192.168.77.1 -> 0a:00:27:00:00:04

Check password for 'john' is 'password'

Found password for 'john': 'password'

ARP: timeout 192.168.77.1We have been running successfuly our first home-made unikernel on an hypervisor!

Conclusion

Takeaways

- MirageOS is quite well-packaged and thought out and mostly works out-of-the-box as advertised. The documentation is detailed and takes the newbie by the hand through the various steps one needs to build all the examples. All in all the “developer experience” is better than with HaLVM,

- I was mostly frustrated by my lack of knowledge and understanding of Xen platform and virtual networking and I am indebted to people from the MirageOS mailing list and IRC Channel #mirage for their help,

- I was also limited by my lack of knowledge of OCaml, but working with MirageOS is a good incentive to learn the language which seems interesting and somehow feels different from Haskell while sharing a lot of concepts.. Finding documentation on OCaml is pretty straightforward and idioms are close enough to Haskell I was not too far off most of the time…

Next steps

I really think the unikernel paradigm could be as important a shift as containers and dockers have been in the last couple of years and as such I really want to keep investigating what MirageOS and HaLVM have to offer. To the best of my understanding there seems to be two different approaches to unikernels:

- A bottom-up, language-agnostic and system-based approach which produces unikernels for any or most kind of unix binaries by stripping down a stock OS and packing it along with adapted libs with the target process. This approach is merely an extension of the existing containers paradigm and is exemplified by Rump kernels and OSv,

- A top-down and language-centric approach exemplified by Mirage and HaLVM where system-level components are actually written in the language thus providing all the benefits of tight integration and focus, and packed with a custom minimalistic OS.

Obviously, the former approach definitely requires less effort and allows one to produce unikernels in a very short time span by simply repackaging existing applications and services. The latter approach is more demanding as it requires expertise in a specific language and building all the needed components, sometimes from scratch, to provide low-level services otherwise provided by standard system libraries. I don’t have much rational arguments, beyond those provided in Mirage’s own documentation, to back my personal preference for the latter: I might be biased by my interest in functional programming languages, especially strongly typed ones, and the somewhat childish desire to master every single part of the system stack.

What I want to do know is:

- Write a truly useful service that could be unikernelised in OCaml: To build on some previous experiments in the domain of distributed consensus, I think having a unikernel-based Raft implementation could be a challenging and interesting next step. Another potentially interesting use case would be to build unikernels for serverless tasks dispatched with something like AWS Lambda but this is not possible,

- Experiment more with solo5, a companion project of Mirage whose goal is to allow running Mirage unikernels on top of non-Xen hypervisors, like qemu and VirtualBox,

- Experiment with deployment of unikernels on cloud providers. There is some documentation and script already available to deploy to AWS which I would like to try.